Arts & Culture May 2018

In verse, fruits of life’s joy and sorrow

Poet Ross Gay to read works in Bennington

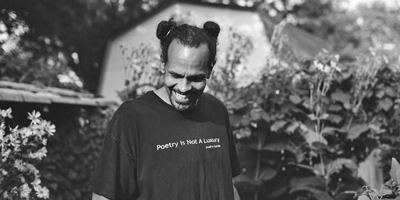

Ross Gay’s third and most recent book of poetry, “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” was a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. He’ll read his works on Wednesday, May 16, at Bennington College. Courtesy photo

Ross Gay’s third and most recent book of poetry, “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” was a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. He’ll read his works on Wednesday, May 16, at Bennington College. Courtesy photo

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

On a spring night in Bloomington, Ind., Ross Gay is planting young lettuces.

Winter has hung on so long, a warm evening feels new -- to stand barefoot in a troweled furrow with the air smelling of earth and stems, and peels in the compost pile.

As he walks in his garden, planning onions and potatoes, purple or red or gold, he is standing near the plum trees where he set some of his father’s ashes when he dug the earth to put in the bare-root saplings:

… poured some of him in the planting holes

and he dove in glad for the robust air.

He tells the story in “Burial,” a poem in his third and most recent book, “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award.

He may share that work or one like it when he comes to read on May 16 at Bennington College as part of the college’s Poetry at Bennington spring series.

In Gay’s writing, life and vigor often run with what threatens them -- like the juice of plums and the death of someone he loves.

“To feel gratitude is to acknowledge the pain,” he said, talking by phone from Bloomington.

In his “Catalog,’ his father is dancing, coming home at the end of a long late shift to share hot wings with him, and lying in a hospital bed.

His friend Don is eating sweet potato biscuits out of the pan as they talk in the kitchen, listening to Nina Simone and walking arm in arm down the block and past the graveyard, before he was murdered.

In odes to buttoning and unbuttoning his shirt and drinking water from his hands, Gay is talking about love and the loss of people he loves, and the anger and fear and tiredness he feels as a black man in the United States.

“It is a corruption of the imagination,” he writes in an essay, “Some Thoughts on Mercy,” as he traces the way it feels to live in a city or a world where many people accuse, where they are hostile, where fear is constant and people die: shot, or collapsing from illness and exhaustion.

The voice speaking in his poems cultivates imagination as he cultivates beehives. That storyteller is alive in his mind and body as he is in his garden, and in his family, and in the touch of the woman he loves.

Gay said he chose the title of the book to hold open thankfulness. He chose it “to acknowledge moving forward, understanding the fullness of our lives,” he explained. “They are complex and rich. Birds are singing outside my window right now, and that’s wonderful, and people I love are in pain. Every day.”

Strength in joy

Gay writes the book’s title poem in the present tense, and it flows with textures and smells and colors and movement. He opens a hive, and bees cling together who did not survive the winter. Gardeners sweat through their shirts and horses buck across a field, and rank spent grains feed the soil and all that grows.

… thank you knitbone and sweetgrass and sunchoke

and false indigo whose petals stammered apart

by bumblebees good lord please give me a minute ...

He said he chooses to practice joy in his writing and in his life, that joy is important for health and strength of mind.

“To exalt what we love, what we adore -- adult joy accounts for, is even made by suffering,” he said.

And in that understanding of life and pain, people can reach out to one another.

“There’s something in terms of the discipline of it, a necessity,” Gay said. “It feels to me that understanding of the richness of human experience contains profound sorrow, and it is a way we are connected to people. As I understand, as I relate to you, as I know you are experiencing pain and sorrow, and will experience it, and you will die … a tenderness comes from that practice.”

His work has touched people powerfully. Michael Dumanis, the director of poetry at Bennington College and curator of this spring’s poetry series, said he first fell into Gay’s work years ago at a bookstore in Cleveland, Ohio. He took Gay’s first book, “Against Which,” off the shelf and stood amazed.

Dumanis recalled his excitement as he read -- individual words he wanted to dive into, ideas brought together that shook him with the strength of his feeling, and the clarity and freshness and perspective in the lines.

He remembered calling a close friend who might have met Gay and saying, “Tell me about him -- I can’t believe these poems I’m reading.”

The poems have stayed with him, years later. Scenes and images come vividly: Two bikers -- two large, heavyset men -- held each other outside a hospital, and a man driving by swerved across the road as he felt that clutch.

In another poem, Dumanis read the shooting of a teenager from the bullet’s point of view.

“It’s strong,” he said. “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life.”

Students and professors at Bennington and visiting poets feel the same way. As he talks with his classes, Dumanis said, he hears anticipation for Gay’s visit, and his name resurfaces in conversations.

Dumanis’ colleague, the award-winning poet Phillip B. Williams, has taught Gay’s work. Monica Youn celebrated his poetry when she visited this winter to read her own, and Gabriele Calvocoressi, who spoke last fall, is Gay’s friend.

They warm to his intimacy and intensity and intelligence. Dumanis felt it with wonder in the poem “Sorrow Is Not My Name,” from Gay’s second book, “Bringing the Shovel Down,” as the poem names some of the world’s thousands of “naturally occurring sweet things.” Their names invoke them, calling them into being. The man speaking acknowledges darkness and fear, but his niece is running through a field, calling his name, and when she invokes his name, it is also sweet.

New seeds

That spirit and acknowledgement move in his recent work. Gay has just finished his newest project, “A Book of Delights.” He has spent a year writing daily essays about things that call to him -- a hundred passages about his garden, his friends, public spaces, and music, books and art.

And now he is working on a book about his relationship to the land, his own land and the idea of the land and race.

He wants to dig into the history of racism in America, he said. He wants to talk about conservation, family farms, forces that have shaped people’s lives across generations — what the land has meant to people who worked in the fields but did not own what they grew or the soil that grew it, and what people have gone through to claim their own land, and how they have lived on it.

He wants to follow his family’s history as sharecroppers coming from the South to Youngstown, Ohio, heading north to farm their own fields. Their story encompasses histories of migration, people who have had access to acres and people who have not. As he imagines the book, Gay turns over the material realities and the psychic and spiritual depths of land: economic value, stability, a place to belong.

His mother’s family were farmers, he said. His mother grew impatiens and lilies, and where he grew up, between the apartments and I-95 near Philadelphia, he knew a wooded area where he would spend time with plants and pick wild raspberries.

He started his own garden when he moved to Bloomington, and he became a board member of the Bloomington Community Orchard, the only orchard of its kind in the country: a publicly owned place run by volunteers and open to anyone who lives in the area.

Hands to earth

Gay’s own relationship to the land pulses in his poems, as immediate as relationships with people. Plants figure largely in his writing, with their own stories. The fig trees in his yard and at the orchard come from his friend Jay’s father, who shows up in Gay’s poem “To the Fig Tree on 9th and Christian.”

Sometimes plants’ names spill together like mint in July, some sweet, some healing, some with beautiful sounds.

“What a lucky job to give names to fruit,” Gay said, savoring some from his “Catalog,” Ashmead’s kernel and moonglow.

In his lines he climbs trees, pruning branches, eating fruit in the sun and spilling the juice down his shirt. He throws his body into the orchard.

“And mulberries, I love mulberries,” he said. “They grow all over and drop fruit in places people are not excited about. One of my favorites in town grows a couple of blocks away, and man, is it prolific.”

The people who keep the yard where it grows are always grateful when he and his friends come to pick the fruit. The berries stain the pavement dark purple when they fall, and they ferment in the heat.

He loves the taste and the picking.

“The act of putting one’s hands in the earth, trying to feel like the earth provides a kind of bounty, is sustaining,” he said. “To know you can do that. To put a seed in the ground and know something will come up, and go to seed, and exponentially reproduce — to feel an abundance, a potential for abundance you can witness and be in the middle of — that’s magic. It’s important to be in the process. Things grow, and things die, and things grow because things die. There’s a lot of coming and going and witnessing — and we’re a part of these processes we spend a lot of time pretending we’re not part of.

“And the pleasure of lying on the ground, smelling stuff, that’s a genuine pleasure. That’s a solace.”

Ross Gay will read his poetry at 7 p.m. Wednesday, May 16, at Bennington College’s Tishman Lecture Hall. The reading is free and open to the public.